What is a penciler, and what is an inker? What is it like to draw comics professionally?

I don't think much has been said or committed to print on these two subjects. Not very much that is very revealing at least, and not a whole lot from a comics artist's perspective.

Artists usually like to talk shop. I know I do. But much of what we artist types discuss isn't even meant for public consumption. So much of it probably would seem overly technical and obscure to "outsiders". And very little of it would be all that helpful or even sensible to curious readers.

That is, unless the "inside story" of how comics creators work were made more accessible by being tailored to that sort of readership.

So, with that in mind, I am going to attempt to do just that--to make it informative and fun to learn about. Well, to make it sensible at least.

But First, A Few Opinions Regarding Opinions...

It's fun to read comics and it's almost as much fun to talk about them afterward! Inevitably opinions form about artists--you know, like who is good and who is not.

Comics fans all have their favorites, right? Fans will talk about this pencil artist, and that inker, and wouldn't it be great to see so and so ink what's his name. That can be lots of fun, too. I used to do it all the time back when I was a young comics collector and fanzine publisher, and I still do.

I'm thinking some of the banter might go something like this: "I loved Jack Kirby's art--but only when Sinnott inked him! Sinnott is great and he makes every penciler look better!"

"No! You're wrong! Vince Colletta is my all-time favorite Kirby inker!" "What? Are you kidding? Everybody knows he is the worst inker in the business! He sucks!" "Does not." "Does so." "Does not!" And so on.

Sound a bit familiar? In case you haven't guessed, I'm still a comic book fan after all these years. I never grew out of it. That's why I write for this blog. Just for the record, Joe Sinnott’s work is on my favorites list too. But, just as sure as I am that I'm not lone in this, I loved the work Vince Colletta did over Kirby!

Being both a fan and a "pro", I get to view things from both sides of the fence, so to speak. That's why I know that the fan approach of simply comparing styles and penciler-inker teams can get you in trouble. Not the kind of trouble that can get you arrested, mind you, but trouble nonetheless.

After all, terms like "great" and "sucks" are not definitive (and neither are the terms "good" or "bad" for that matter). In fact, opinions are subjective by their very nature, right? "Everybody knows"? Not exactly iron-clad proof, right? And artists have their opinions too.

I don't agree that Vince Colletta was the "worst inker in the business." And while we're on that subject, I've even heard before that Vince didn't care about his art.

Are observations of this nature based on fact? Not really.

Yes, Vince Colletta was the fastest. That's a given. Vince's output was enormous. Hey, so was Jack Kirby's! But over the years Vince Colletta inked hundreds of my favorite comics. Yes, hundreds. And back in the 70's Vince inked dozens of my covers at D.C.--and he made every one of them look better!

I knew Vince personally and worked very closely with him at D.C.'s offices when he was the art director.

Back then I didn't just work in a nearby office. I certainly wasn't just minding my own business and keeping to myself at all times. I visited him and interacted with him on a professional basis almost daily--and I can tell you he was highly skilled and incredibly knowledgeable about comic art.

I remember a particular time that he took a few moments in his office to show me some art pages that he was inking over my pencils. As he showed me those finished pages he said he put extra time and work into the inking and hoped that I liked what he did.

And, you know what? I got the distinct impression that Vince was proud of his inking on that job and that he was actually trying to impress me! Now, I ask you--does that sound like someone who didn't ever give a care what other people thought of him as an artist?

As an artist I have gotten more than my share of accolades at comic book conventions and in print and on the internet. I get criticized too. And it's rarely done by readers who are "in the know" or can even approach being experts!

They know what they like, sure enough, but usually they describe how they feel in hyperbolic terms.

To further underscore my point, I'm going to be totally fearless here for a moment and use myself as an example.

Often I get compliments from sincere fans like "you draw better than Neal Adams" and "your art is more dynamic than Jack Kirby!" You believe that? Hey, I wish!

I get bashed in the fan press or on blogs because supposedly I don't have a "style of my own" or because I have "too many styles". No style that is "my own"?--that's a bit of a stretch. Then there are my occasional "homages" from the 70's that are often, let's just say...under-appreciated.

So opinions can be really out there. Like the time at a comics convention, when Jim Shooter stopped by to visit my table in artists' alley and he said to me (quite unexpectedly I might add): "Rich, I always thought you drew like God!"

That's a bit more than over the top, no? And I mention that here because I honestly don't recall a single time when Jim ever even gave me a compliment back when he was my boss at Marvel Comics!

So what's all that stuff about, really? Does just saying things like this make any of it true? Of course it doesn't. It's mostly about emotion, not critical expertise--and it's really neither here nor there.

So forget what "everybody knows". That's just consensus thinking anyway, and often it's really no thinking at all.

Let's delve into the subject of who does what and how in the comics--from an insider's perspective. Once you wrap your head around how complex and creatively demanding comic book art really is, it's not so easy to make sweeping and sometimes unwarranted judgements.

You can take what I say herein with a grain of salt if that's your mindset. That's okay too. I'm not telling anybody what they should think, or like or dislike.

The Art Of Drawing Comic Books--If You Are Not An Artist, It’s Probably Not What You Think It Is!

Did you know that in the comics business, except in rare instances, the penciler rarely knows ahead of time who will be assigned to ink his work? That's been my experience anyway. Even nowadays those kinds of decisions seem to always get made by somebody else who is not directly involved in the creative process.

You would think things would be different. I rarely, if ever, had my choice of inkers--and if I had my way I would have had all my art inked by Dick Giordano and Frank Giacoia!

Most of the time I would hand in my work not knowing what would happen to it. In a way, what would happen next was always a bit of a crapshoot. So I would just cross my fingers and hope for the best!

I have also worked on both sides of the editorial desk. I know from experience the challenges of being "the guy in charge." As editor I have done the hiring of artists and writers for the publisher and I have put many creative teams together. I can assure you, it's not an exact science.

I have hired Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Dick Ayers, Frank Giacoia, John Severin, Gray Morrow, Alex Toth, Jim Steranko and many other outstanding talents. So I know comic book production from that insider perspective too.

My own professional observation is that some pencil artists are easy to ink and some are very difficult. And why is that? Well there are so many variables. Let's get into that.

If we were to embark on an imaginary quest for producing the ultimate and perfect art team (like such a thing were actually possible!), I know that questions like these would likely come up:

Does the inker understand the drawing well enough to follow what is indicated without stumbling or ruining portions of the art? And if so, does the deadline allow for enough time to do the job properly? Will the inking and pencilling styles be compatible?

Like I said, there are lots of variables. And egos are involved, too. Artists have their own ideas about what works and what doesn't. So, concerning which penciler works with which inker and how well that will all work out--is that all something put together flawlessly and totally on purpose?

Back in the 70's and 80's at both D.C. and Marvel comic book production was particularly hectic. The margin for error in estimating how long an assignment would take was quite narrow. So the pressure was always on--and when it came to deadlines, I can assure you that nobody had a sense of humor about it!

I recall John Verpoorten (Marvel's production manager back in those tumultuous days at the beginning of my career) greeting me with his characteristic salutation:

"Hey Rich, you got those pages for me?"

Of course I did. But being young and feisty, I asked him: "Hey, John, you want the job fast or do you want it good?"

Not unexpectedly, his answer was: "I just want it done!"

And that's what professional artists in comics do--they get it done. Nobody does it perfectly. Usually it's fast and it's good--and occasionally it is excellent!

But always it must be on time.

How It's Done...

Since this is "Secrets Behind The Comics", let's get into some specifics about how it is done. Not every comics artist works in the same manner so I will stick to discussing things that relate to how I work.

I never assume that anything I draw in pencil will be fixed by the inker. That's not the inker's job anyway. What I am hoping for, of course, is a confident and polished ink rendering that follows my drawing and enhances everything that I have indicated in pencil. That would be the ideal.

That's not always what I get. But for the most part I have been fortunate over the years to have worked with many gifted inkers.

In case you're curious, I'll mention here a few of my favorites: Dick Giordano, Frank Giacoia, Vince Colletta, Dan Adkins, Romeo Tanghal, Bob McLeod, Joe Rubinstein, Klaus Janson, Al Milgrom, Joe Sinnott, Rudy Nebres, Tom Palmer, Tony Dezuniga and Jerry Ordway.

There has to be at least a few of your own favorites in that list, too. Those artists each have their own distinct styles and I don't mean to imply here that they are the only inkers that I think are good or excellent.

They are all immensely skilled and highly accomplished. I mention them because these are the artists that I feel are most compatible with my work and who at various times have rendered accurately and stylishly (but without noticeable distortion) what I intended in my drawing.

So what specifically is the job of a penciler? Let's explore that. Along the way I'll try my best not to get too cerebral or overly technical.

As a pencil artist, besides always aiming for very clear storytelling, I strive for clarity of thought and "solid" drawing that even a less than skillful inker would still be able to follow.

Depending on how realistic a style I am working in, I indicate all the lighting and shadows and textures, and I strive for detail and to make things look specific--a gun looks like a gun, a tree or car or a building looks like what it's supposed to be, etc. Nothing is allowed to appear vague or misleading. Finished pencil art is just that--finished.

On the finished pencil page ideally there should be no drawing anomalies. There should not be any guesswork on the inker's part about anything I drew. That's what I shoot for anyway. Also, the inker should not be required to draw anything in pencil before applying ink to the art--ever.

These are all things that I think every professional artist is mindful of. A good command of the human figure and ability to draw a myriad of characters of all ages and ethnicities is of course mandatory.

Notice that I haven't even touched on pencil line technique.

Aside from textures or special effects and the like, I tend to use as little technique as possible ("feathering", side of the pencil shading or smears, etc.). That is, I do use lines and shadows, but not in any kind of overtly stylish way to show off technique or draftsmanship.

What You See--And What You Don't...Or, "You've Just Been Erased!"

Here is another way to look at it (or not). This is something for any aspiring pencil artists out there to keep in mind.

My advice is to be prepared and accept that all of your pencil lines, no matter how carefully done or how beautifully crafted, are going to be covered completely in ink. In other words--you guessed it. It’s all going to disappear!

Yes, the cold reality is that none of it will ever be seen in all of it's original splendor!

Inking As Drawing...

Now we come to the job of the inker. Misunderstanding what an inker does can can cause all sorts of distorted ideas. Sometimes the inker gets too much credit for the look of the final art--sometimes, not enough.

Every team effort of pencilers and inkers is a compromise.

There are no "super inkers" who make every penciler look great no matter whose art they ink (I wish there were!). That is just a gross exaggeration. Some combinations do work better than others. Generally inkers do a judicious amount of embellishing and make "improvements"--but not all of them do. And nobody is perfect.

So let's take a look at what inkers do.

The inker is responsible for the final look of the art--to make it as sharp and attractive for reproduction as possible. In that sense, they do correct things as they work. For example, a stray line, a missed detail, or some appropriate added black areas--things like that. Pencilers who ink their own work do this too.

Nobody even attempts to duplicate exactly all of the subtleties and nuances of the pencil work . That is not only not desirable, it is practically impossible.

What the inker is expected to do is faithfully render the drawings in ink. He is not expected to redraw what has already been drawn.

Which is not to say that that doesn't involve drawing. It does. So every professional inker should of course have a good grasp of the basics of drawing.

Why is that essential? Everything has already been drawn, right?

Well, consider this: a good professional inker will never merely trace pencil lines with a pen and brush. That's not inking. It's just tracing. Trust me, that approach would only produce mediocre results.

A really substandard inker (one who is not competent or whose drawing skills are not up to professional standards, that is) may get work, but not for long--and certainly not on a regular basis!

Okay, in the comics a few bad inking jobs may happen (and it's a wonder that there are not more!). That almost never occurs on a top book. And I don't know of a single instance where a totally inept artist was ever afforded the opportunity to make a career out of it!

So a skillful inker's job is to give artistic expression to something that is already there--but at the same time, as an artist he superimposes his own stylized version of things on to that.

Yes, some are "heavy-handed", some are a bit overly neat and precise, some are loose and "organic", etc. It takes all kinds!

Now, occasionally there may be minor corrections or refinements that are done in the inking stage (and some of these get done later in the production stage when it is called for).

However, what the ink artist is not there to do is to alter the dynamics of the figures or the action. He shouldn't have to significantly "fix up" anythng. Nor is it desirable for him to depart dramatically from what the pencil artist intended (still, this will always vary from inker to inker).

So how important is the ink stage? Well, the very best inkers can make a mediocre penciler look competent, a good penciler look great, and a brilliant penciler look like the genius that he is (and we all wish that would happen a lot more, right?).

I can't speak for all professionals, of course, but it is pretty much a given that nobody involved in the production of a comic book is an intentional slacker or is goofing off or faking it. You can't fake being a professional. Well, actually you can--but certainly not for very long!

Ask any artist in comics what it's like to draw comics for a living. They'll always tell you how easy it is, right? Um, nope. Not if they're honest about it. It's long hours and hard work. When the work is handed in to the publisher, an artist could die of old age waiting for a compliment. The truth is, even with the so-called superstars, those artists who make a career of it are overworked, under-appreciated and underpaid. That's how it really is.

More About What An Inker Does...

I also ink my own work. Most pencilers do not. And I think that many pencilers in the comics business tend to be too tough on inkers and often judge them too harshly. Pencilers should at least try to do what inkers do--and maybe then they would lighten up a bit!

What learning how to ink taught me was a greater understanding and appreciation of artists like Dick Giordano and Frank Giacoia and Vince Colletta. Knowing these artists personally also gave me a valuable "insider" view of how each of them worked.

I'm self-taught, and as such I had to suss out a lot of what was needed on my own. Still, I had much to learn, and those three professionals I just mentioned taught me firsthand a great deal about the craft of inking.

With every pencil job I learned something new. By observing and studying what various inkers did over my pencil work, I saw a lot of areas where I could improve my drawing and make my next pencil assignment look even better.

Inking Is Drawing--And Thinking!...

As I mentioned earlier, Inking is actually drawing in ink! Well, think about it for a moment--for a penciler that is initially a very scary prospect. It means working in a permanent medium, and--no way around it!--having to nail every detail of what has been depicted the first time. With no mistakes! I don't mind telling you that part of it was very intimidating at first.

Yes, minor mistakes can always be corrected with "white-out". That's your "safety net". While that can be helpful, it's not a panacea. The last thing you want is a lot of ink corrections showing up on the page because you "dropped the ball" too many times--even if you're inking over your own pencil work.

And if youre inking another artist's work, chances are you know the guy and will see him again, so you don't of course want to tick off the penciler!

So, How Do They Do It..?

Inkers do not think like pencil artists. They don't have to. It's a whole other mindset really.

The ink artist doesn't have to be concerned about the esoterica or minutia of how a comics page is conceptualized--that's the penciller's domain. By the time the inker comes on there aren't any real problems left to solve.

So if the pencil artist was really thorough, he has taken care of business and has done all of the tough drawing work. Taking into account different styles and pencil techniques, the ideal pencil page is one where everything on the page has been clearly delineated and is relatively easy to follow.

That doesn't mean the inker just dips his brush in ink, cancels his brain and just lets his hand fly and do the thinking for him! It's hard work that requires a lot of solid drawing knowledge and intense concentration.

Since literally all of the pencil art will be erased at a later stage, what has been rendered in ink should be at least as good as what was "underneath" it--and hopefully even better!

To accomplish that requires a vast amount of skill and--yes!--a whole lot of thinking! We're talking hundreds, even thousands, of decisions that occur during the work process--all of this being accomplished with verve, a steady hand and unwavering confidence.

The pencil artists always seem to get the most attention. Okay, that's with good reason, and that's how it's always been. But you want to know what I think? Just to be able to ink consistently well and fast is probably one of the most valued and underrated skills any artist can possess. And those inkers who achieve excellence are a veritable treasure!

Some Work Methods...

Frank Giacoia and Mike Esposito showed me how to work very methodically. We got to talk shop quite a bit. I would hang out in Marvel's bullpen from time to time, and they gave me a lot of tips and shared many bona fide tricks of the trade.

A lot of planning is involved. So it is always preferable to be highly organized and work in a methodical way. Let's get into that.

With both Frank and Mike, we're talking an enormous amount of experience and know-how. As an inking team they rendered many of the covers I drew for Marvel's British reprints.

When these two artists worked together you could hardly tell that the finished product was the work of two inkers!

I always admired Frank Giacoia's expressive brush work and his bold yet lyrical rendering on figures. I could just imagine that, to Frank, it was like music-- where he was the virtuoso composer who surely understood there are no "bad" notes, only wrong ones and right ones.

Frank once pointed out to me that when you do it right--inking, that is--"It will always looks like you did more than you did. But it's actually less work than you thought it would be."

To that he slyly added: "There is a trick to it, though. You have to really know what you're doing!"

That was a bit of Frank's spry sense of humor. But he was right.

There really are no shortcuts to the craft of inking. That's what I found out, and that's what he was getting at. You can't get there before you get there!

Here is more or less how Frank and Mike’s work process went (according to how it was related to me).

The inking process is broken down into careful steps and stages--in other words, the inker takes things one step at a time and is always being mindful to never get ahead of himself.

The very first and crucial step is to "outline" the figures and objects. This "outlining" would be very basic ink line work that is just enough to define forms. This first step would lay the ink foundation--everything afterward would be built on that.

All of the finesse and brushwork and detailing would then be done in later steps (what Frank would call "the fun stuff"). You could look at it as a sort of "flesh" that would go over that "skeleton" (outlining). And that's not just with the figure work--everything gets this systematic and orderly treatment.

Now if you're not an artist, you might assume the inker would render the first panel on the page to a finish and then move on to the next panel, right? That seems to make sense, right? I know that's what I thought way back when I was still in the amateur stages. But that's not at all the case.

The professional way to do it is to work the whole page--to move around, all the while carefully pacing yourself without spending too much time on any one area at first. Just sort of "feeling things out". Thinking and feeling, thinking and feeling--letting things develop a little at a time.

Also it would not be unusual to have three or four pages going more or less at the same time with the inker (or in this case, inkers) bouncing back and forth as the "muse" dictates.

Okay, so that's enough technical stuff.

Did I mention that working while in a relaxed state is essential? That is particularly applicable to comics artists since they work under lots of pressure.

An artist will never get good results if he gets all cramped up and tense. Let that happen and you just end up struggling to draw anything, whether it's in pencil or ink--and that is something a professional will never do!

More About Vince...

As I mentioned before Vince Colletta took me under his wing and taught me a lot about the craft during my seventies period at D.C. .

I was just a young pup back then and my aim was to learn all there was about creating comics--so I was never shy about it! I asked tons of questions. I won't go into all the "nuts and bolts" stuff (and there is a lot of it!), but I found that all of the "old school" inkers worked in much the same way as I have already recounted.

Vince inked a lot of my work. But he also was the only boss I ever had who gave me my choice of inkers. This happened on a pencil job I did on Batman for Detective Comics. One day we were in his office at D.C. and Vince asked me: "If you had your choice, who would you like to ink this?" I said: "Anybody I want, right?" "Just give me a name.."

I gave it some thought and then replied: "How about Berni Wrightson?"

And Vince got him!

Incidentally, I noticed back then something about Vince's inking. To me his pen work often looked like brush work--and vice versa. Well, Vince actually used both, and almost interchangeably! I got the opportunity several times to watch him work. I can tell you, there is no substitute for seeing how it is actually done!

As he worked he explained to me that his view was that whatever an artist can do with a brush he should also be able to do with a pen.

Drawing Is Organized Thought...

I remember an anecdote Mike Esposito once related to me about his experiences back in the heyday of the Andru and Esposito team. I just have to mention here that Ross has always been one of my favorites.

Anyhow, the following sounds like it might be true even though I knew Mike was often prone to exaggeration just to make a point.

According to Mike, Ross's pencil work was "quite the opposite of minimalism". He told me that conceptually it was all there on the page, but there was so much of it!

I never actually saw the art Mike was using as an example, but he said that Ross would draw with so many sets of lines that the pages almost seemed to vibrate! To ink it, Mike said that he had to just pick out one set of lines and wing it.

I'm going to point out something now that may be viewed as somewhat of an anomaly. Nevertheless, it is true.

Every comics artist knows that it's not about the lines.

The lines are what you use to get you there! It's not about straight or crooked or beautiful or how many lines you use or how few.

Concept comes first, before the hand of the artist starts to move. An amateur will scribble away--but an accomplished professional artist conceptualizes first.

On another level it's all energy really. So my guess is that those "vibrating" Ross Andru lines Mike referred to were the energy and vitality of Ross's organized thought!

"Zen" And The Art Of The Comic Book...

As far as inking goes Dick Giordano and Frank Giacoia set the bar for me. It was Dick who taught me how to ink assertively but without "showing off."

I worked with Dick closely on quite a few projects for Peter Pan records (remember those?) and we collaborated on a lot of illustration work for the Special Olympics. I even spent some time at his studio in Connecticut back in those days when he operated under his company name "Dik-Art".

Dick was the consummate professional. His creative approach was a sort of "Zen" applied to comic art (he didn't call it that, but that's my take on it) where the inker's process is a "technique with no technique".

That's not to say that the inker's style and individuality gets hidden or suppressed. It's more an interpretive approach that brings out the best of what is in the pencil art with a minimum of lines and pen and brush technique.

For example, Dick told me don't use three brushstrokes where one will do it. Never go over your lines to "correct" them. Whether it's pen or brush you're using, make every line expressive without weakening or distorting what the pencil artist drew.

Also, he admonished, an inker should never "noodle" or use extra crosshatching (patterns of lines that form shading) where it is not called for. Every ink line is a decision. Even the "negative space" (where there is no drawing) is important!

You've probably heard the old saw "less is more." That was Dick's approach (and it was very much like Frank Giacoia's, too!). He would always put clarity and precision first.

One of his favorite expressions was "inking is thinking!" I think that Dick had an extra advantage, too, in that he was also very proficient as a pencil artist.

Red Circle & Marvel Recollections...

Over the years I have seen a lot of original comic art pages by a lot of comics artists. I saw the very first pencil pages of Barry Smith and Paul Gulacy (incredibly detailed work!) as they came in to John Verpoorten's production office (which I visited often). Lots of Jack Kirby, John Buscema, Herb Trimpe, and Gil Kane art. Sounds like a comic book fan's dream, right? For me, it certainly was--but it was more like school.

From what I have observed, it is evident that the fastest pencilers have always been the ones with the least "finished" penciling style.

I don't mean that necessarily there was something lacking or that the artist was careless or lazy. What I mean is that more was deliberately left up to the inker--as was always the case with Jack Kirby and Gil Kane.

With both of these dynamic artists, the streamlined style they worked in emphasized form and content and action, with a bare minimum use of shading or shadow or indications of lighting. This kind of pencil work, for me anyway, is the most difficult and challenging to work on.

I never had the opportunity to ink Gil Kane's pencil art, but I did get to collaborate with Jack Kirby on a cover for Blue Ribbon Comics featuring The Shield for Archie/Red Circle.

I remember Dick Ayers (who I had hired as a penciller) telling me back in those Red Circle days about his experiences at Marvel when he inked a lot of Kirby art.

Dick meant no disrespect to Jack, but he related to me how Jack's pencil art always required a heavy amount of "finishing". The way he described it, at first glance it would look like everything was there. But much of what Jack pencilled on the page amounted to stylized lines that were mere "suggestions" of things rather than what they were supposed to represent.

As the inker Dick had to do a lot of "embellishing" (in ink, but also in pencil, to bring the drawing up to a finish before inking it). Also a lot of corrections and refinements and added detail were required--probably partly due to how fast Kirby penciled, which was always very fast (as much as five pages per day, I have heard--on a good day the most I could ever manage was three, and not on a regular basis!).

Anyhow Dick estimated that the inking took him two or three times as much time per page as it did for Jack to pencil. And he wasn't bragging or complaining--that's just how it was in those days.

While I always appreciated Joe Sinnott's slickness and precision line work over Jack Kirby pencils, as an artist I always favored the more detailed and visceral look of Kirby and Ayers (both teams totally worked, especially on my favorite Marvel title, The Fantastic Four!).

By the way, I got a good sense of what Dick was talking about when I inked the aforementioned Jack Kirby cover.

Around that same time at Red Circle when I was Managing Editor, I had occasion to hire Steve Ditko to draw The Fly. That was a real "fanboy" choice on my part, but it provides another good example.

I remember my dismay when those pencil story pages by Ditko came into my office. I was somewhat disappointed because of how unexpectedly "unfinished" the work looked.

Ditko apparently worked a lot like Jack Kirby and Gil Kane. Nothing fancy, no extras, just the bare bones. So when I inked that first job by Ditko I did a "Dick Ayers" and embellished a whole lot!

Some Reminiscing On My Very Early Work...

Back in the early 70's when I first broke into comics I knew fairly well how to ink my own work already. It didn't come easy, though.

When I first began to learn how to ink (and this was long before I even had anything printed) I had many wrong ideas. I can tell you from experience that at the beginning, in my first few efforts, I was totally lost.

It's a good thing I took up my inking studies early in my youth! As with any discipline, once you get down the basics the learning curve starts to work in your favor. But experience is the real teacher!

In my very earliest attempts at inking I remember that I was lucky if I could ink anything straight (with or without a straight edge) without the ink leaking and bleeding and making an ugly mess.

I was working back then on the larger original size--approximately 12" x 18". In fact, my first professional work ("George Washington Attacks Trenton!") was done that size. By the time I got my second pro assignment the industry had just switched over to the 10" x 15" standard size.

It took literally hundreds of hours of practice before I started to get the knack of it. Of course I didn't practice on actual professional pencil work, since this was before I had ever seen any originals from the comics.

I worked in different pencilling styles and sometimes there would be more than one version of the same pencilled page--all of it was experimental. The actual work was serious, but it was really more like play.

When I was ready for the inking stage, I would then ask myself: "What would this look like inked by Wallace Wood?" Or, "How would Angelo Torres or Reed Crandall do this?" And then I would render my version of that. Of course it was all guesswork, but it was great fun!

About the same time that my inking skills started to amount to something, I was also practicing doing my own lettering. Not that I ever aspired to be a letterer--but surprisingly practicing the lettering helped me to gain some early technical mastery.

Lettering way back then was done using Crow Quill pen nibs (the ones for calligraphy with chisel points or blunted tips). To draw accurately in ink using a pen (the ones with the flexible nibs) was not as easy as I expected. Still, it was not nearly as difficult for me to master as working with a brush. Getting predictable and consistently decent results using a brush took mounds and mounds of practice!

My first professional inking over another artist's pencilling was on a Man-Thing story by Jim Starlin. By then I did have a good grasp of the craft of inking. And actually that was an absolute must--because realistically you don't get professional work as an inker if you're still in the practicing stages!

Here’s an interesting side note: Al Williamson inked most of his straight lines freehand, even if a straight edge was used to pencil them in first. Yet Al's rendering always looked flawless! Yes, it's true--artists do know how to draw straight lines without a ruler!

Okay, there you have it. I actually got more into inking than I did pencilling--but I hope I succeeded in providing some enlightening and fun information about both.

So who is "good", or "better", or "best" in the comics? Well, you should know by now that that's actually a bit of a conundrum.

The penciler and the inker each work their wonders in their own manner and chosen style--each of them unique in their own way.

It should at least be clear now just how much of the actual artistry that goes into creating the comics is not so immediately evident in the printed work.

It's a lot like the technological wizardry of the behind-the-scenes magic of the movies, where the alchemical processes that make comic art what it is remain mostly hidden. But the magic is there! And I have to ask you--Is that not a truly amazing phenomenon?

Oh, yeah--one more thing...

Remember what I mentioned earlier, that every single comic book cover and story page that you have ever seen has actually been drawn twice!

After reading this installment, and keeping that in mind, the next time you pick up a comic book to read and to admire the art you should be able to appreciate it at least twice as much!

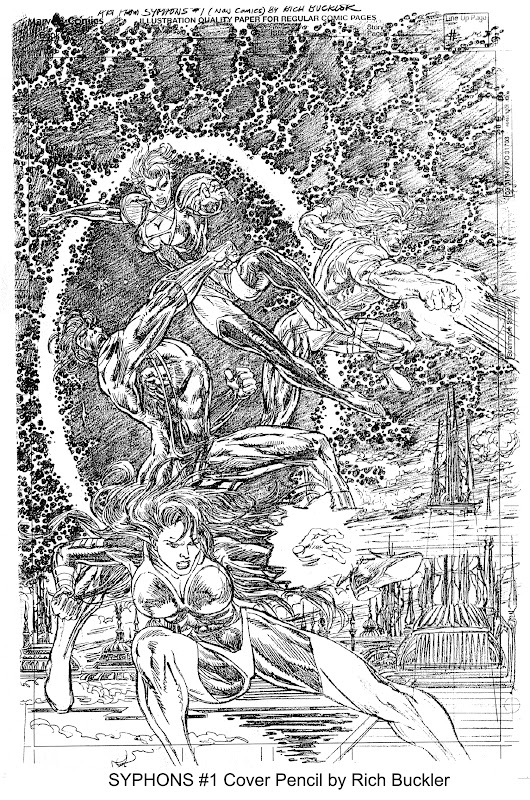

Be sure to visit Rich's Hermetic Surrealism website at www.richbuckler.com and of course his comicbook-related site at www.bucklercomicart.com. And if you're interested (and who wouldn't be?) Rich does commissioned sketches, drawings, cover recreations and paintings. You can contact him via e-mail at bucklersr@aol.com!

Dear Rich,

ReplyDeleteLoved your last post, on comic book surrealism. This is something I've often thought about, but you put it into words.

In Marvel, Angar the Screamer caused much surrealistic havoc, and, as a child, I loved your work in Daredevil # 101. I first read this story in British Marvel, where the images seemed much more powerful, depicted in black & white. Your fight sequence in this story was so visceral that, as a child, when Angar grabbed Daredevil's uniform, I could almost feel it in my own hand. You obviously put a lot into creating the sense of dynamism & movement, in this long sequence.

I totally agree that Frank Giacoia was perfect for your pencils. Frank also excelled himself (inking Sal Buscema) in the Nova story, featuring the Firefly (Nova #8 or # 9). This story involved a character (the Megaman)being smothered by the attentions of a female alien entity, to such an extent that he was losing his own individuality. The art work in the story symbolised the Megaman's loss of individuality by depicting him with no facial features. A genius artistic concept like this should get more recognition.

Back to the subject of surrealism, another one of my surrealistic favourites (also involving Frank Giacoia), in Marvel, was Captain Marvel # 42. The strangeness of this story involved its juxtaposition of spacemen & cowboys, suffocating on a world losing its atmosphere. The joke ending of this story spoiled it somewhat, but luckily, as a child, I didn't see the ending, having only bought the first part, in a British Marvel, so, to me, it remains a surreal classic.

What's notable is that this story (like your Daredevil # 101, and another one of my surreal favourites, Karate Kid # 15), featured strange "lobster men", depicted by the art team. Do you remember what the significance of these lobster men was, in the 70s? Were they inspired by something in popular culture, at that time?

A final surrealistic fave of mine, at that time, was Shade the Changing Man #6.

I know your treatment of comic book surrealism was far more serious & detailed than merely the conventional interpretation of the term, so please don't think I haven't read your excellent discussion.

Have you any thoughts or memories about DD #101, or the strange "lobster men", appearing as either hallucinations, or a "real" characters, in other comics?

Phillip Beadham

Many, many thanks for the excellent post.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Mr. Buckler. Very informative. You were one of my favorite Groovy Age artists.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the great post; I just spent my entire lunch-break reading and enjoying every bit of it.

ReplyDeleteGreat post! - digging the Giacoia and Williamson bits - and way to show some love for Colletta- I dig his inks on Tuska and Toth and early FF Kirby (and his full art 50s romance stuff)...

ReplyDeleteRich, could you please relate any behind-the-scenes stories on the Archie/Red Circle comics of 1983 - 1986?

ReplyDeleteTotally agree about the Kirby pencils, which is why it was such a shame when he stopped using pro inkers and hired greenhorn guys to trace his pencils without doing any rendering. You can really see the difference when he left Marvel, both in the 70s and later in the 80s.

ReplyDeleteMike Royer is the best inker Kirby ever had!

ReplyDeleteSee those artist were wrong, Kirby didn't leave anything out, that was just his style!

That's why Royer was best, he understood Kirby's style and let it shine through!

All the stuff that Royer inked of Kirby at DC, the Fourth World, The Demon, Omac, all that material is absolutely excellent!

It's some of the very best work of Kirby's entire career!

Can't believe they aren't making movies of it!